Episode 5: Morel Doucet on climate gentrification, magical realism, & art for advocacy

For Episode 5 of The Heart Gallery Podcast, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer talks to Morel Doucet.

Morel is a Miami‐based multidisciplinary artist and arts educator from Haiti. He creates captivating ceramic, illustration, and print works that examine the realities of climate gentrification, migration, and displacement within the Black diaspora communities. Listen and learn from the magical Morel Doucet above and in all the podcast places.

The podcast transcript is available below.

HW from Morel: “Being an educator in the museum space I like inquiry. How inquiry works is that you make a visual observation of the work in front of you. Instead of coming to an immediate conclusion, you analyze a work based on its various aspects before you form a conclusion about the work. Another way of phrasing it is, “don’t judge a book by its cover”. Extend this beyond art too: give people grace, give them an opportunity. By being patient, you may uncover something new.”

See the work of Morel’s mentioned artists: Didier William, Cornelius Tulloch, & Chris Friday.

The Saan people mentioned in the question about ceramics.

Connect with us @moreldoucet & @rebekaryvola.

Thank you Samuel Cunningham for podcast editing.

Thank you Cosmo Sheldrake for use of his song Pelicans We.

Podcast art by Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer.

And be sure to read about & view Morel’s three pivotal creations below…

3 heart moves with Morel Doucet:

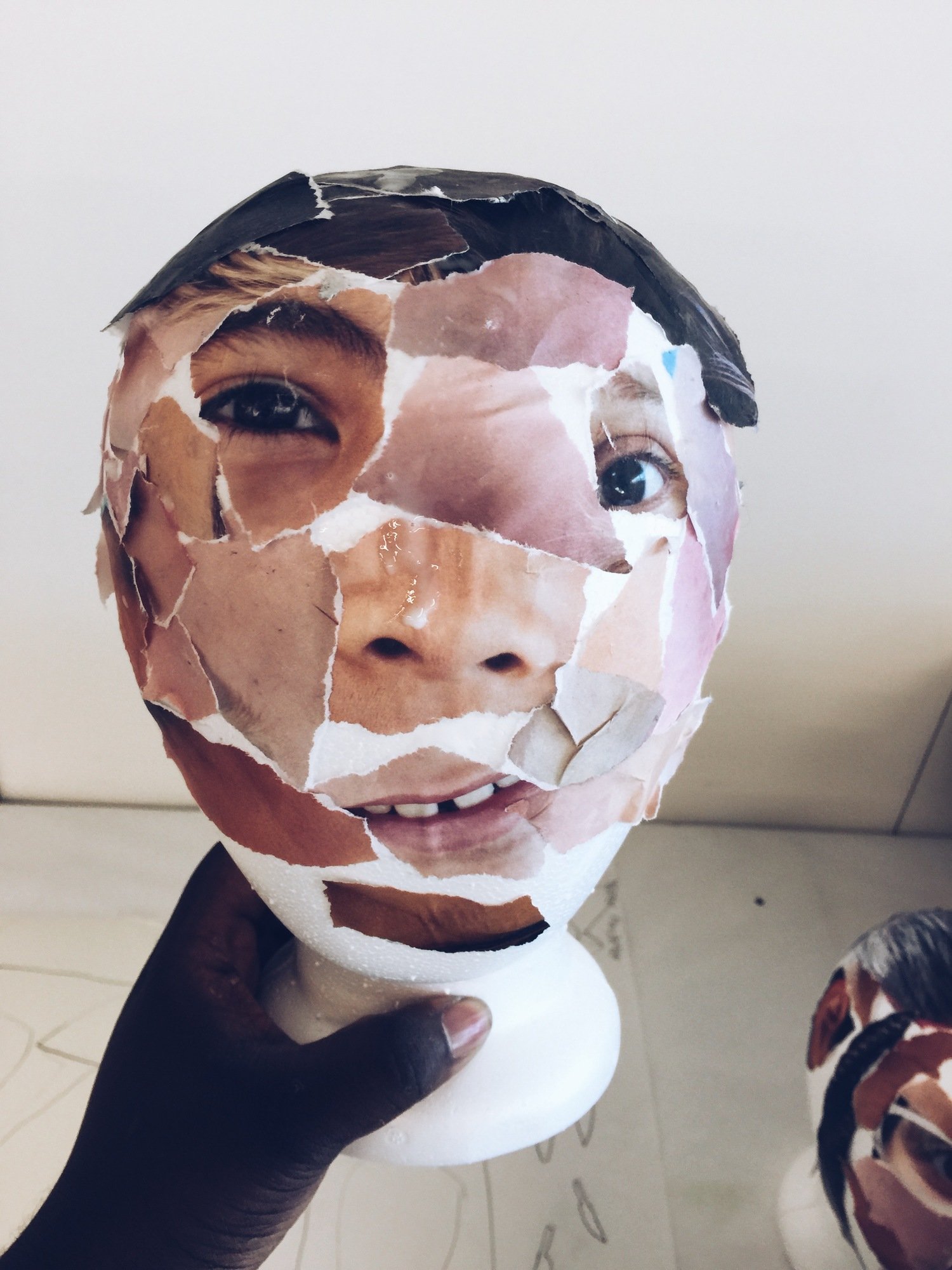

To provide a visual accompaniment to your listening of The Heart Gallery Podcast Episode 5, here are 3 milestones of Morel’s that are significant in some kind of way to his life, perspectives, and career. All photos courtesy of the artist.

#1: Art Education from Perez Art Museum to ICA Miami. 2015 - 2022.

“One significant milestone for me has to do with my work as an art educator. Specifically, when I left the Perez Art Museum (PAMM) for the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami (ICA Miami). I was part of the original team when PAMM opened in 2013. After 5 years at PAMM I was able to take the knowledge I’d gained there as an educator and implement it at ICA Miami. Being a young educator on the team that built PAMM up and then getting to go to another institution and use the skills I’d gained at another from-the-ground-up museum creation effort was significant for me.”

Photos from PAMM and ICA Miami programs:

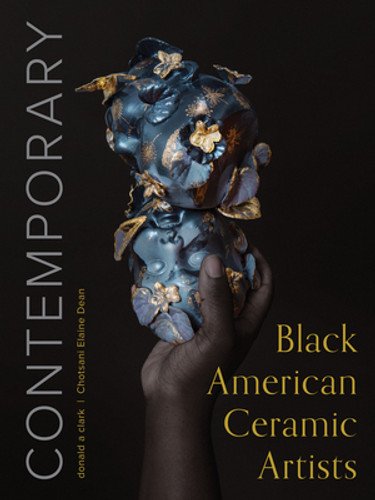

#2: Feature in Black American Ceramic Artists, by Donald A. Clark & Chotsani Elaine Dean. 2022.

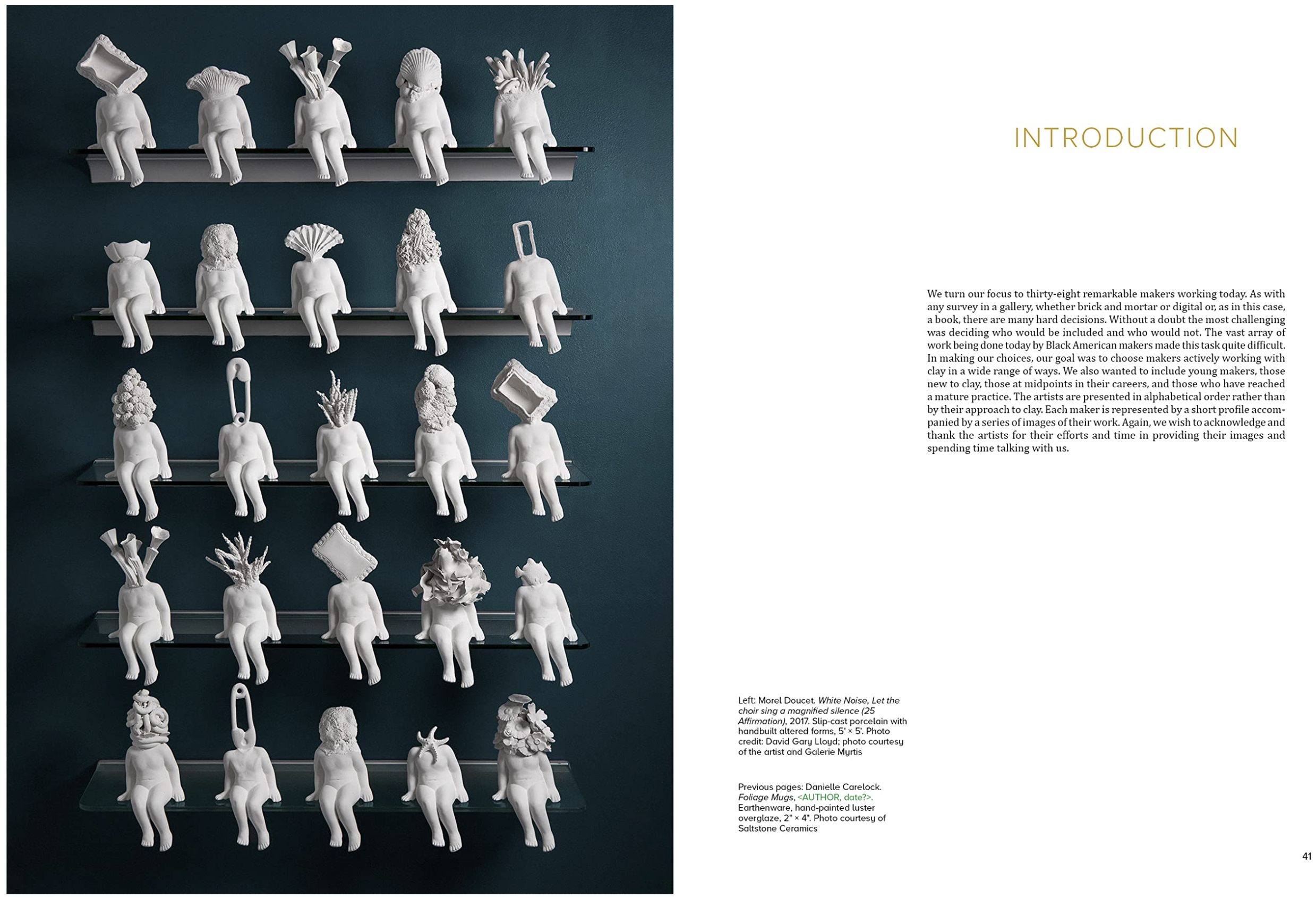

“The second milestone moment that I feel really good about is [having my work featured in] the book Black American Ceramic Artists, by Donald A. Clark and Chotsani Elaine Dean, published by Schiffer Craft. I worked on this with my photographer, David Gary Lloyd. We shot the photo you see on the cover at David’s house: he had a creative idea for the shot and then much later it happened to end up on the cover. The book is the first of its kind. The aim is for it to be a comprehensive collection of the work of Black ceramic artists from across the US. [This first edition features 38 Black Americans and] the plan is for the book to grow over time and to bring in more and more artists.”

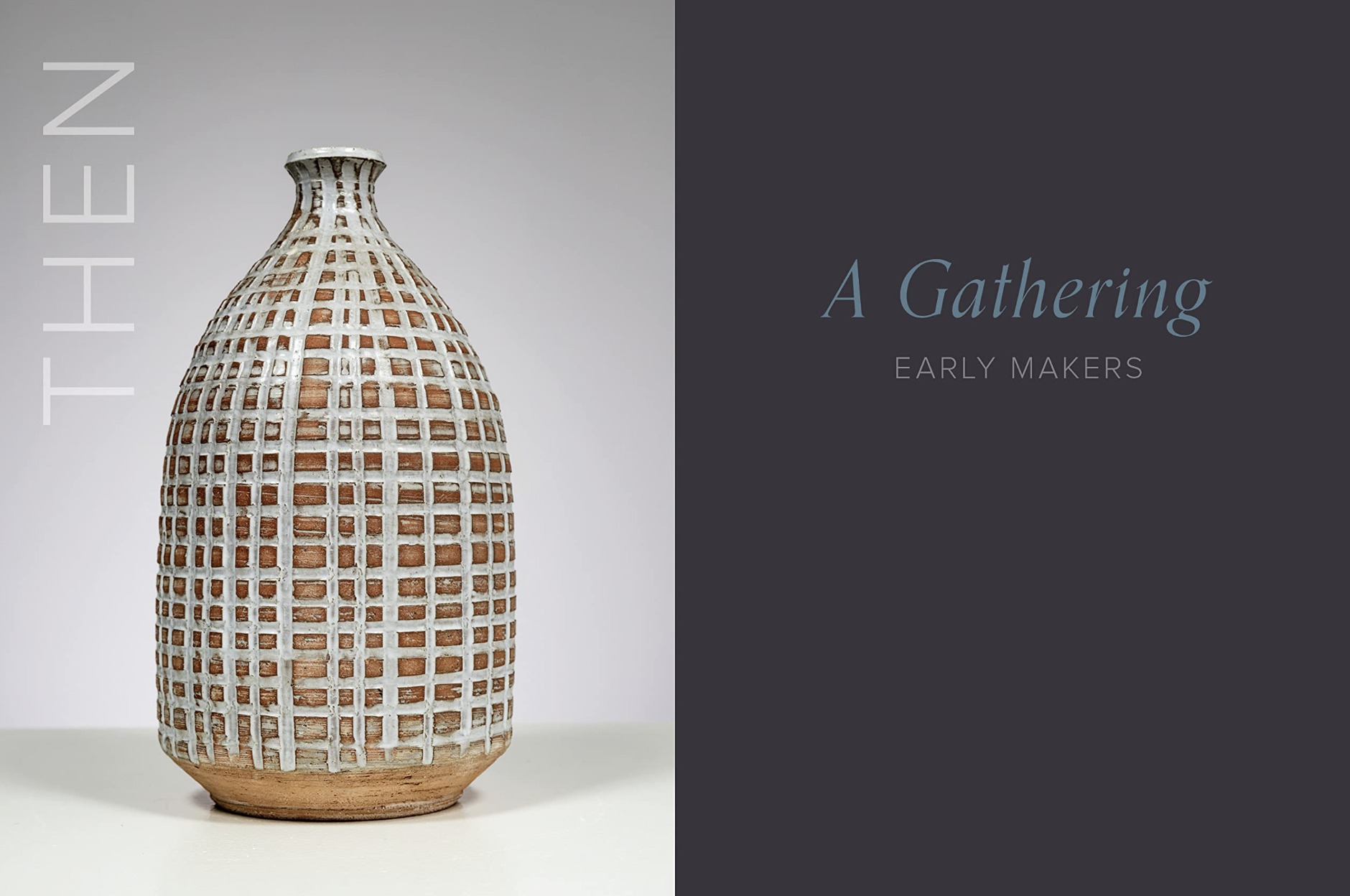

#3: Anthropology essay on Miami’s changing landscape. Upcoming in 2023.

“This milestone is upcoming, was a long-time in the making, and is a big deal for me. I have my first essay being published in a catalogue of essays supported by Art Change Us USA. It’s an anthropology essay about the Miami area and its changing landscape called Secrets that the Wind Carries Away. I was super nervous to take on this project. The gatekeepers are at Duke University Publishing, and it was a big deal for me to have them approve my writing, and, in fact, to request that I contribute.”

Follow and connect with Morel to see updates about this project and others!

Podcast transcript:

Note: Transcripts are generated in collaboration with Youtube video captioning and ChatGP3 and are not extensively edited.

[Music]

Hello and welcome to episode 5 of the Heart gallery podcast, with me, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer.

I am an artist, creative advisor, and visual communicator and I’ve worked primarily with climate and humanitarian organizations for the last decade. I also have a personal art practice where I explore relationships between individuals, other living beings, and our planet. I created this podcast to inquire into the various roles that art can play in helping us create deeper connections with our surroundings and others - both human and more-than-human. Listen to hear from other artists engaging in these interrelationships with all kinds of approaches, philosophies, and hopes for the future of humanity and our earth, and learn about different ways that art can help create change.

This episode is part 1 of a two-part Miami climate change series that I was lucky to be able to record in person. This week I talk to Morel Doucet. Morel is a Miami‐based multidisciplinary artist and arts educator from Haiti. He creates captivating ceramic, illustration, and print works that examine the realities of climate gentrification, migration, and displacement within the Black diaspora communities.

Morel’s works offer narratives that address the contemporary reconfiguration of the Black experience. His compelling imagery captures environmental decay at the intersection of economic inequity, the commodification of industry, personal labor, and race.

Morel has been nominated for an Emmy and his work has been featured and reviewed in numerous publications, including Vogue Mexico, Oxford University Press, & PBS. His artworks are in the collections of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, the Tweed Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami, the Plymouth Box Museum, the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art, Microsoft, and Facebook.

As an Arts Educator, he is interested in working with young audiences to instigate curiosity, sensory perception, and visual literacy.

In this episode we talk about how he brings his art approaches to Miami's climate issues, including climate gentrification, and we discuss how to engage ethically with corporate entities. Morel also shares about the history of ceramics and his experience connecting to his Haitian roots. I’m so grateful to have gotten to meet Morel in person for this conversation…

[Music]

R: “Welcome to the Heart Gallery Podcast. It’s so nice to be here with you in your beautiful studio surrounded by so much color and texture. I'm actually looking around for emerald green and frost green, and I'm seeing some greens. Before we started recording, during our sound check, Morel was telling me that his favorite color is green, specifically emerald and frost. Maybe when we do the walkthrough of your work later, you can share some of those greens with me.

I've read a number of your interviews, and you speak so beautifully and eloquently. It's a joy to hear you speak, and I feel like our audience is in for a treat. I wanted to start at the beginning - well at one of your beginnings - when you and your family emigrated from Haiti to the United States.”

M: “It's such a pleasure to be here on this podcast, thank you for having me. As a first-generation Haitian-American, I was born in Haiti and grew up around a time of political upheaval. My father was an anesthesiologist, and my mother was an educator who would travel from different regions in the northern department of Haiti to teach math. Sometimes she would walk two hours to a site, and other times it would be a drive.

My mother migrated a lot, and my father was working in the hospital as a doctor when he was arrested and put in prison under the reign of the Haitian president. It was a very traumatic experience for my mom, as there's no system that cares for prisoners in Haiti. If you're arrested, your family has to provide care for you, which includes bringing food for breakfast and lunch. However, sometimes the guard would eat the food that you brought for the person in prison.

After this tumultuous time, the US eventually intervened in the political affairs of Haiti, and my parents were given the option of getting political asylum. Within a very short amount of time, they had to pack everything they owned and were transported from Haiti to Mobile, Alabama. I was around three years old at the time, and I remember the journey vividly. We had to ride on the back of a truck carrying loads of charcoal, and at a certain point, we had to maneuver through rivers and streams to get to our destination.

When we landed in the United States, you know, it was a complete culture shock. I grew up calling my grandfather "Dad" and my mom by her first name, because my parents worked challenging schedules. It was so hard for my parents. In the early days, I would cry every time I saw a plane fly above. I just wanted the plane to come pick me up right then and take me back to Haiti. After living in Mobile, Alabama for six months, my parents moved to South Florida and have been living in Miami for over 20 years. Moving to Miami in the early 90s was a huge Mecca for many immigrants, not only Haitians but Cubans, people from South America, etc. Miami became this conglomerate of different immigrants from different walks of life trying to find a new opportunity at the American dream.

Being the eldest of two other brothers and a child of first-generation immigrants, a lot of my childhood was spent trying to navigate day-to-day life. With my very broken English, I had to help my parents understand very important documents and sometimes translate. Sometimes they were given incorrect information. These are things that later in life affected the way I do certain things and how I advocate for people.

In the midst of all this going on around me, the beauty that I did not know at the time was that in the 90s, there were these magnet art programs that were popping up everywhere in Miami. I had an art teacher, last name Goldman, who saw raw talent in me and pulled my mom aside one day to tell her that they're specialized schools that would take my raw talent and cultivate it. By the time in the 90s, there was a district push to create arts enrichment in these schools, and so I auditioned and got into a magnet art program. At the time, it was called Ransom Park Elementary School. Since then, the program has unfortunately been disbanded and doesn't exist at this school anymore, but by the time in the 90s, it was one of the schools that had a magnet art program. So, from fifth grade, when I entered the magnet art program, I stayed in that system all the way up through high school. I had a specialized experience in middle school in the Arts Magnet, and then the same thing for high school as well.

The high school that I went to was called New World School of the Arts, which was a very competitive school. You entered based on the merit of your work, as well as having a certain level of academic rigor. You had to be high functioning, either A's and B's, and really had to be a high-performing student because the rigor of the school was at a level of excellence. It was no small feat, either, and the commitment was a huge sacrifice. So, you can imagine that if you were in a regular high school, you would have homecoming, football games, etc., but going to this Arts High School, those were things you wouldn't experience.

My freshman year of high school consisted of waking up at 5 o'clock in the morning, taking a shower, getting ready, and being at the bus stop by 5:40 in the morning. I'd catch the school bus from the end of my neighborhood. The school bus would drop me off at the metro station. I would take the train to downtown Miami, and then I would walk to school to be in class by 7:20 in the morning. I did that for two years consecutively before my parents moved and my mother became a condo owner, so I no longer needed to catch a bus. There was a bus that I could catch in front of the condo that would take me to school in downtown Miami.

But for two years, I would wake up at five o'clock in the morning and get home at 6:30 in the afternoon. That was what my day consisted of as a student. In that time, a lot of students dropped out of the program because it was very rigorous, and the commitment was too much for them. But for me, being an immigrant without access to many resources, it was a way out that I saw for myself.”

R: “What ages are we talking here?”

M: “So high school, we're looking at age...?”

R: “Oh, this started in high school.”

M: “Yes. We're looking at ages 16 to 18 at that time.”

R: “That's some foresight for someone who's 16. What were you imagining at this time? What kind of future were you imagining for yourself?”

M: “In high school, I accelerated academically as well. So I graduated high school with a weighted GPA of 4.45, which was impressive. I gave myself permission for two options. I told myself I could either pursue a career in medicine like my father or I would pursue a career in the arts.”

R: “And was that decision based on the narrative in your head about you being gifted? The seed that was planted by this teacher?”

M: “It was a little bit of that. By going to one of the top performing arts high schools in the whole US, the teachers would breathe life into you. They saw talent, and by my junior year of high school, so many students had dropped out of the program. My graduating visual arts department went from about 40-something students to only 16 of us graduating. My entire graduating high school class was only 109 students, between visual arts, dance, theater, musical theater, and voice. It's a very intensive program, and not for the everyday student.

But going back to your question, throughout my experience in middle school, you know, seeing how my parents were struggling, really hit me. My mom, at one point, she's working two jobs, and so I saw how hard she was working. And also, I did not want to experience the life she had. But then also, I did not want to disappoint her because she sacrificed so much for me. I knew I wanted to make her proud. So, I knew I could pursue a career in medicine or somewhere in academia because I had the grades and the knowledge. But the arts was a chance that I was willing to bet on myself. I did have teachers, one of my advisors, was trying to sway me to go the more practical route, 'Go into medicine, you'll get a job.' But I really wanted to become an artist.

And so secretly, I applied to mostly art schools. And then she said, 'Well, you should apply to maybe a community college or maybe one of the state schools here in Florida.' But I knew that's not what I really wanted, you know? Yeah, I knew where I wanted to go. And so, I applied to 15 schools during my senior year of high school, and I got into 13. And then I narrowed down the 13 to my top seven, and then I brought it down to my top three. And so, my top three all gave me scholarships.

One of the schools, which was Kansas City Art Institute, at the time when I was a student, I was their highest decorated student in terms of scholarship. So, I had every top award they had, the school had given it to me because they're really incredible over there. And my two best friends in high school, they were twins, both of them got to Kansas City as well. But I didn't want to go to Kansas City. My heart would just say, 'I don't see myself living in Kansas, you know?' It's like just imagine if you're living in Miami, then you have to leave Miami to live in the middle of Kansas. You don't want to do that, you know?

My heart was in Baltimore. You know, I had alums that graduated a couple of years before me. I was talking to them, and Baltimore made sense. It was in proximity to New York, it was in proximity to D.C., Philadelphia, Virginia. And so based on where the artists that were thriving, artists that inspired me, all of them were in New York. And so, Baltimore was just at the tip. I knew it was accessible, so it made sense for me to go to Baltimore.

I didn't have the financial money to go visit colleges. So even though I applied to 15 schools, I didn't get to see a single one of them because I didn't have the money. For me, I actually went on to Google Maps, and I did a street view, and that was my college tour of the campus, with a street view of the school.”

R: “I do love street view, like it is quite incredible. One of my hobbies is going on street view, like going to new countries and new cities, but that was all I had, you know? But that’s all you had.”

M: "Yeah. And I had the option of going to prom or using that money towards my first year of college. So I'm like, 'Prom can wait. College is so much more important.

By saving my prom money, I ended up buying my plane ticket and getting the resources I needed as a first-year student. I flew to Baltimore and, at that time, I was very much an introvert.

I came to MICA as the recipient of their presidential scholarship, which is one of the top awards that the college gives out to a student. The school made a big deal out of it, which made me uncomfortable because that was never me. I've always been in a corner doing the work, but now the spotlight was on me.

After getting adjusted to that, I realized that because of my status, I was never graded the same way as my peers. I was always treated a little bit harder by my teachers. I always had to operate on a certain level because of my scholarships, and because I was coming from one of the top-performing art schools in the entire nation. I had the technical skills in painting, drawing, ceramics, and every other medium you could imagine. From high school, I dabbled in it, so my okay was never the best in my teacher's eyes. I was always graded a little bit harder, and I do appreciate that.

My high school teacher warned us that by the time we start college, we'll be so far in advance than our peers in college, and we didn't really understand it until we got to college. We realized that we were so far advanced than a lot of other students. We were told before going away that we would be treated a little bit differently, and now looking back, I have more fondness for those teachers."

R: "I was telling you that my family and I emigrated to Canada. I was almost exactly the same age as you, probably around three. One of my experiences growing up was trying to figure out, “what is community”. Of course, I wasn't articulating this kind of question when I was little, but looking back, I see some of the internal mental struggle I had was, 'Okay, what is community? How do I fit? Where do I fit?' Canada right now is grappling with its colonial past and present.

Now I'm living in the United States, we can talk all about the different kinds of social issues here in the U.S., but I also saw myself as somebody coming into a place that was not my own, which also factored into my grappling with this sense of belonging and what is community. I wonder how you navigated through that because just jumping ahead to the art that you've been creating, that I've seen a lot of over the last five to ten years, really incredible work, and a lot of it from my perspective seems rooted in community. So I wonder if you could share about your experience grappling with some of those questions, or maybe different ones, and what your conception or how your own conception of community developed.”

M: "Growing up in South Florida, it was not very popular to be Haitian. Being Haitian carried a stigma, and there was a false narrative that AIDS started in Haiti, which was never true. That was one of the false narratives that was passed around.

In the 90s, Haitians were called boat people because a lot of them were immigrating here on boats -”

R: “In an incredibly dangerous way, right?”

M: “Many were perishing on that route. Haitians were reduced to being seen as boat people or as having AIDS if you were Haitian. The idea of representation didn't start to emerge until the mid-2000s, and a lot of it was through entertainment media. Seeing people like Wyclef Jean on TV, seeing that there are Haitians who are doing well and contributing to American society, changed the narrative.

Growing up, I tried to hide my accent and got really good at code-switching, which is the active process of disguising your voice or manner of speaking. I could sound really white over the phone, and it allowed me to get my foot in certain doors. But people were taken aback when they met me in person. I stopped doing that in college, and now I show up as the authentic version of myself. But as a method of survival and trying to assimilate into American culture, code-switching felt like the right thing to do at the time.

Even in college, I remember a distinct moment when I was on a train heading to campus with a friend. A black lady who grew up in Baltimore was listening to us talk and was impressed by my eloquent speech. She said her grandson, who lived in California and came to visit her during the summer, always got made fun of by his cousins because he didn't have a certain accent or diction. She called it "good English." I was surprised by her compliment because I was very particular at that time about how I spoke and how I wanted to present myself.

I wanted to hide my Haitian identity and assimilate into being perceived as American or just as black. I did not want to be seen as Haitian. My group of friends knew I was Haitian, but most people just saw me as black.”

R: “You mentioned that you started to move away from code-switching when you were in college what was the impetus for that?”

M: “So what happened was, um, two things. My minor is Creative Writing. Throughout my coming to terms with my thesis for Creative Writing, I developed a chapbook of 100 - it was about 125 poems that I wrote for my thesis for Creative Writing. And in the beginning of this book, I was writing of poems I struggled a lot because I just feel I was trying to find a writing voice. So, you know, I was looking at different diction, you know, like, um, grammar, Southern Accents, and none of it was really sticking to me.

And when I started to kind of like re-read these poems, but reading it in Haitian Creole in my head, I realized that there was a beauty in the language. You know, Haitian Creole, at the core of it, comprises of seven various languages that makes Haitian Creole. So, we're looking at Portuguese, that's French, that's the Taino kind of mixed into the language. And I decided to just look into Haitian history, and I realized that, you know, within my growing up, I was, I did not know Haitian history. I did not know my history. And there was a reason why, you know, Haitian history was not taught in school and more specifically in the U.S.

And so when I started to look at that research, I realized that, oh, Haitian history is studied and celebrated in Africa, studied in South America. Haitians have had a global impact, and none of this has ever been taught to me. So, in a sense, when here in the U.S, they talk about the Louisiana Purchase, the French had territory they sold the territory, but it was never mentioned that they sold the territory in order to finance the war to go against the Haitian people.

Um, and so Haiti altered the course of American History by forcing France to sell this territory in order to finance the war. And they, the French eventually lost that war as well. That was one of the global impacts that Haiti had on American history. Um, Chicago was founded by a Haitian person. And when you think about Louisiana with the Creole and the Embargo was placed on Haiti, if you look at the flags in South America, the red and the blue, um, those colors were inspired by the native seeing the Haitian.

Once Haiti got their independence, they not only freed themselves, but the Army, the Haitian army started fighting freedom for other people that they wanted to liberate everybody that was of color that was black. And so Haiti, the Haitian army went through parts of South America and started liberating these other countries. So, we think of these flags in South America that have the red and the blue. That's from the Haitian flag. They integrated those colors into that. And so, through my research, through studying this, I realized that, oh, this narrative of Haiti being the third world country, um, there's more to it, you know?

There's a reason why this embargo was placed on Haiti. The Haitian government paid the French what is equivalent today at 22.3 billion dollars. Um, so if the Haitian government got that money back from French as reparation, um, what would that do for the economy? What would that do for the country? Inconceivable how much they could do. And so, in a sense, Haiti paid the ultimate price for gaining their independence, for helping free other people.

And so while these other nations have thrived, Haiti has been very much positioned in a way where they did not really see the repercussions of that freedom. So when I talk about Haiti now, you know, I say Haiti is the first black Republic. When I think of ideas like the movie Wakanda, the second movie for Wakanda, there's a scene where they go to Haiti and they're introducing the new son of Chadwick Boseman in the movie.

He's hiding in Haiti, and it was like an homage to this legacy of what Haiti is.”

R: “Do you recommend the movie?”

M: “yeah, I would recommend the movie.

So to go back to your question, through me doing this internal dive into my history, into what it meant to be Haitian, what is Haitian history, and understanding the global impact of Haitian history, then I told myself that I would no longer try to assimilate. I'm going to show up as the authentic version of myself, and that ultimately is why I stopped code-switching. I told myself that I was enough, my culture is proud, my culture has impacted the globe, and I have an obligation to walk into space as the authentic version of myself.”

R: “So beautiful. And I wonder, as you're going through this journey in your college years, was this also when you started to explore themes of the black diaspora within your art?"

M: "Yes. Throughout my time in college, I was always fascinated with what Western culture would deem as primitive, savage. But when I looked at these cultures, I realized that they're not primitive. They're in tune with the environment. They know how to create medicine, they can cure hunger, care for pregnant women. Because we don't pump medicine and vaccines into their system, we say they're primitive, but they're not. They're actually much more in tune with the land and their environment. I stopped believing that narrative that these are primitive cultures. Just because you don't have an LED light above your head that's on at the flip of a switch does not mean you're primitive. It means that you have a different way of life.

Um, and so when I study these cultures, I just started seeing the beauty of them and how they were just in tune with their environment. And that became this area of discovery and this hybrid method and the work I was doing during college.”

R: “You just mentioned the environment piece. I'm curious where your love of the environment came from because you have this thread of the environment, of nature, of human-nature connection that I see and that I've heard you talk about. Where did this come from? Was this really truly like a part of this college-age discovery process? Or did you have an earlier interest and connection to the environment that you tapped into?"

M: "So when you look at my work, the earliest inspiration of the environment stems back from my grandfather. My grandfather is a farmer. And so, growing up, I was always around him, watching him farm the land, raise 11 kids, and put all of them through school through farming. It was incredible, but also, I came to have this understanding of our connection to the land. As a farmer, you farm with the female. And so, if you take something, you want to put something back into the Earth. And so, watching my grandfather farm, having this intimate exchange between the land and the per and the outcome of that, it's kind of one of the earliest references of what land is and why I reference the environment in the work.

And then more recently, in the work that I make right now as an artist here in Miami, there's aggressive gentrification happening across the city. Some developers would buy a property and they would tear down the house in order to just pay a land tax with the payment of property tax. And so, when you're looking around, the only things that are staying behind in these vacant lots are the plants, the trees, the bushes, the flowers. And so, in a way, the only thing that stays behind in certain neighborhoods is that. And so, by using the plants in my work, it's essentially using this idea of memory. It's magical realism. I'm using the essence and the energy of what you think used to live in that particular space. I was honoring the spirits or the ghosts or the memories of that space. And so, when you look in the studio, as you see reference to flora and fauna, the flora and fauna is paying respect to that."

R: “Speaking of gentrification - that is rampant here and in so many cities, in so many places - you also, in your work, explore climate gentrification, which is a concept that's relatively new to me. I'm here with you in Miami, it's my first time here. I've heard you describe Miami as the front lines of climate change. Through my own environmental science and climate change studies, that was sort of like the mythology as well of Florida and the city. But climate gentrification is new to me.

I was just reading about it thanks to you. So, thanks to you, you're raising awareness about this issue to others who are visiting, coming in. And climate gentrification is this idea that people who are wealthy and whose properties, residences, businesses, etc., are being threatened by rising seas here in Miami and elsewhere, they have the luxury to be able to move to higher ground. And what they're doing through that action is they're displacing other communities who don't necessarily have the ability to pick up and go. So, these communities are being disbanded, are being torn apart, rent asunder, and who really knows what is going to be happening… can you share more about your exploration in this space and maybe just share more about this issue and how it's manifesting here in the city?”

M: "That was an absolute dead-on definition of gentrification, of climate gentrification. So, thank you for saying that.

Um, I've lived in Miami for over 20 years. The neighborhood that I grew up in is called Little Haiti, which is the mecca of Haitian culture. So, many Haitians that came to Miami in the 80s and the 90s started off in Little Haiti and they have branched off to other parts of the city. Little Haiti has always been a majority Haitian community, but in recent years, through studies of land elevation, it has become one of the higher enlisted communities in Miami. As a result, developers have been canvassing the neighborhood and buying properties in multitude. One developer would come and buy as much as 13 properties in a one-year period. Other tactics they use are buying properties and eventually forcing a tax increase.

If someone is making $30,000 a year and their property tax goes up, they can lose their home if they can't pay the property tax. There are multiple tactics of how this development and gentrification is happening. Another way is through offering money. If a developer offers $1 million to buy a home, that might sound like a lot of money, but the land is much more valuable than that. A developer can take that same land and flip it around and make a billion dollars off of that same property they bought for $1 million. This is happening in the main strip near Little Haiti, where there is a huge site that is supposed to start development, and the developers are trying to rebrand the neighborhood as Magic City. But those who grew up in Little Haiti have known it as Little Haiti, and the developers are trying to come in and rename it, rebrand it and provide this new dream of what the neighborhood can look like.

The city commissioners and residents have proposed having affordable housing or mixed housing, but the developers don't want that. The last issue was that they wanted to have a Community Trust where they would throw a lump sum of money into it and the community would decide how they want to use that money, but the developers don't want to do that either. They want to come into the neighborhood, build what they want to build, and not have to be told what to do or how to do it.

R: “As an artist who grew up in these spaces and over time learning more about the issues facing various communities, does it feel like it's your responsibility to be raising awareness, shining a light, embellishing with flowers and creating these depictions, these visual narratives about what you’re witnessing? It seems almost heavy to me for you to feel like it's your responsibility.”

M: “In the early days of my research and the work I was producing, it was definitely about raising awareness of this issue. I would go to these town hall meetings, hop on these Zoom calls, and when it came to ideas of representation, they were mostly white or Hispanic people in these meetings. There were no Black or Haitian immigrants in those decision-making spaces. After talking to peers and people in the community, it wasn't that they didn't care about what was happening, but because they didn't have the luxury of being in these rooms. If you're in a constant state of survival, then how can you enter a room if you're not even sure if you can make it into that room? If the roof is leaking over your head, if you can't afford food for that month, your basic needs are not being met. So, oftentimes, these people are left out of the conversation.

In my early work, I was an advocate for those who were not necessarily in these spaces. But as I've been producing work over the last several years, the narrative has shifted slightly. Because the topic is so heavy, I'm now looking at ideas of black joy and leisure in these neighborhoods. Behind me, there's a work that I'm creating for my solo show. It's beautiful - there are chickens, dogs, a rooster, two boys, and a gentleman. The work speaks to ideas of Afrofuturism, time, and space. It references land but is also very cosmic in the environment. Blackness exists in time and space - it's infinite. There's joy and memory in these spaces. The new work I'm developing is looking at the idea of rest, of what rest looks like, and who these people are. Why are they in these neighborhoods? A lot of the work I'm developing now is referencing that.”

R: “That piece behind me is so whimsical and it makes me think of the term you used earlier - magical realism. I wonder if you can share more about magical realism. I had the honor of spending about a week and a half in Haiti for a work project at one point. Through my colleagues at the Haitian Red Cross, I learned a little bit about the magic that permeates Haitian culture - this sort of spiritual, maybe religion-tinged, magical culture.”

M: “It's a culture of many threads - there's the deeply religious, either Christian or Protestant, those that practice the religion of voodoo, but then there's also mysticism that's imbued in the culture. As a result of that, a lot of stories are imbued with different qualities. The work I'm creating depicts beings that have no facial features, just a silhouette that embodies a cosmic energy. That energy looks like flora and fauna. It's this idea that if you look at a leaf, there are mathematical principles in that leaf. The same principles are happening in nature and are replicated in the work through the depiction of flora and fauna.”

R: “I wonder how you stay connected to your Haitian roots since you were so young when you emigrated. Have you managed to maintain those cultural ties? How does thee Haitian community that you're exposed to here contrast that with any Haitian community that you might be connected to back in Haiti as well?”

M: "Yeah, so one thing that I'm really thankful for is, you know, my parents made it their mission for me to speak Haitian Creole. Um, and so, I speak Creole very fluently. Um, I can read it phonetically as well. And I'm very close with my mom's side of the family. And so, through new technologies like WhatsApp and FaceTime, um, I'm able to connect with family back in Haiti. And then, in terms of the culture here in Miami, um, I feel like it's still relatively close to how Haitians would typically go about their day-to-day back in Haiti. And because there are resources in the city, um, if you're a new immigrant, if you're a new Haitian coming to Miami, then certain things are a little bit more accessible than if you came here in the early '80s or in the '90s."

R: “Oh yeah, and just to go back for a second to this idea of rest and how you were speaking about that in response to my question about just like the heaviness of having to raise awareness about issues that are so pressing and considering this label that Miami has in Florida in general has as being like the front lines of climate change or like the ground zero of climate change in the United States, where sea levels are rising here and storms and rainy seasons are becoming more intense. And thinking about the value of art when you are in the middle, almost literally - or sometimes literally - of the storm…”

M: “it's a really beautiful question. So, I came to that answer because, you know, as artists, you know, art can be very ephemeral. And so, for me, I came to that answer through my exploration of ceramic.

Actually, ceramic as a medium is the only medium that intersects history, economics, and time. Um, when an archaeologist goes onto an old big site and they dig up these shards that are left behind, we can understand the dietary needs of that culture, we can understand the medicine that they took. Um, we can look at if there are designs on that ceramic piece, we can piece it together and see a story. Um, ceramic intersects history, you know? And then, in terms of economics, with porcelain, ceramic is one of the only materials that had the same monetary value as gold at one point in our human history.

As a symbol of status, as a symbol of prestige, if you went to somebody's house and one way of them showing that they were sophisticated or refined, they would have a piece of porcelain somewhere in the mantle or in the entry of their home.Seeing that, 'Oh, I'm sophisticated, I'm super cultured by having porcelain there.'

Then going back to the idea of magical realism, ceramic has been here since the formation of the universe, so that cosmic particle is in the clays in the soil. And so, by using this material in my work, I'm using time, I'm using space. And then, once the work is created, it goes under this transformation from this raw material into a final state. And then, that final piece can live over a thousand years. So, when I'm no longer here, the work that I produce in ceramic will still be here. It can survive a house fire.

Um, and so, going back to your question, I realized that as an artist, you know, the work that we make becomes a signifier of the time that we're living in. And so, when I'm no longer here, the work that I'm making will hopefully be here to tell the next generation of what we encountered, what we've learned. and hopefully they can use it to change and inform their future.”

R: “That’s very lovely. You make me also think that your work for you might be a form of like self-care. Of course, self-care as a concept has become kind of silly in our society. But I'm thinking more about spiritual care, about safeguarding your internal landscape, so you can show up for the communities you're connecting with and creating works for, and for family and so forth. Can you speak to whether or not your work performs that function for you? And how else, in any aspect of the climate crisis or as an artist, do you prioritize self-care?”

M:”Right now, I'm actually on that journey. I've been working as a museum educator for over 10 years and doing work as an artist. So my time has either been spent teaching or producing work as an outlet. Now that I'm working full-time as an artist for myself, I'm discovering what that looks like for me and how I can implement it into my day-to-day practice. That means waking up a little later, taking time to eat a good breakfast, exercising for 30 minutes, and reading.

I'm a huge advocate of reading. Right now, I'm reading about Mexican pottery, but really I'm studying ideas of gods from the Aztec and the Incas. With my ceramic work, I've been looking at West Africa and the San people who archaeologists believe are the oldest humans on this planet. They have brown skin and Asian features, so when people see my ceramic work, they look Asian, but they're derivative of this African tribe. After studying African culture for so long, I'm now looking at Mexican culture and seeing what are the aesthetics and different symbolism they're using, and hopefully that can influence some work I'm going to be making in the future.”

R: "Okay, beautiful. So, self-care. You're reading, and do you feel like community is a part of self-care?"

M: "Yes, community is definitely a part of that for me as well. In the last several years, I've become an advocate for other artists. I've been very fortunate to have opportunities early on in my career as an artist, and I'm using my experiences to hopefully help other artists that are on that journey as me. So, whether that looks like helping them work on a contract or what predatory practices to avoid from galleries or institutions, I'm using the things that I've learned along the way to pass on the knowledge to other people.”

R: “I saw that you're also collecting art from other artists who are younger, who are maybe coming from lesser-known communities and spaces, and working on different types of issues that are maybe less mainstream or maybe not so New York-based.

You're sharing your collection publicly as a way to not only share the work of these artists but also to shine a light on some of these predatory practices that other collectors sometimes conduct.

I wonder if you could share more about collecting and predatory art practices and how people who want to support young artists, especially those that are working on climate and social change issues?"

M: "Absolutely. As I've mentioned, I've been slowly collecting art as a new collector. Collecting art is a commitment because when you think about it, artists put time and energy into creating something. So, when you purchase a piece of work, it's not just a monetary exchange or transaction, it's an energy exchange. You're agreeing in this licensing that you're going to live with this work in your home, so you're essentially taking a little bit of that artist's essence with you to have inside of the home.

I've been very intentional in who I've been collecting, and so I look at artists that are young and emerging.

By me collecting a small piece from this artist, it's me giving them validation. I'm giving them their flowers that I think their art is something really compelling. If this small acquisition can motivate them to continue making the work that they're making, then let that be.

As far as advocating and helping artists with predatory practices, I think it's an industry problem. I have peers that are in really terrible gallery contracts that are hurting them. I have peers that are unsure of how to go about gallery representation. I have peers that are going through legal issues with corporations or companies. And I realize that one thing that our school does not teach you is how to be a successful business person.

Art School shows you talent, they show you skill, they show you that. But my crash course of how to do my taxes with a one-day class before graduation when I was in college, oh gosh. And they're just like, "Yeah, by the way, you gotta do this something called tax and you should do this once a year," and that was like the extent of what that was.”

R: “That's awful. I struggled so much for taxes and it's just so sad”

M: “And so for me, as somebody who's been really blessed to work with a variety of different brands from Facebook to Ciroc, to name a few, I'm learning as I go. And so if I can take a knowledge or if I can take experience, I'm like, "Listen, this was a really great opportunity, and moving forward, these are some things you should base or advocate for for your contract." Or, "Did you really look at this contract before you agreed to it?

Because there's some really problematic things in this contract that should be revisited or revised." Contracts are now negotiable, and these are things you should look for.

And so as an artist who's transitioning from emerging to this mid-career stage in my life right now, I'm realizing that it's going to keep happening. And if more artists become vocal about it, hopefully we can have a change in the industry, yeah.”

R:“So yeah, that's fantastic. Yeah, I'm so glad that you're out there also as an art educator.

And just to go back to one thing, not to put you on the spot with this one, but you mentioned that you've collaborated with Facebook and I think a couple of other bigger corporations, and how do you square that for yourself? Do you feel like there's any contradiction there given your values or not?”

M: “That's an excellent question. So one thing people always ask me is, from the outside looking in, how do you find these brand collaborations? And I tell people the honest truth is, I've just been dedicated to building a story that was authentic to myself. So the work that you see online, the work that you see in the studio is the authentic reflection of what I truly value. And as a result of that, opportunities have come my way through the stories that I'm telling.

So when brands like Facebook, for example, reached out to me four years ago for an opportunity to collaborate with them, the budget wasn't right for the project and what they were looking for. And so even though it would have been a great opportunity, I had to turn it down because financially, for what they wanted, they didn't have the budget to execute the project. And so I was just like, you know, it was a great opportunity, it did not make sense, and so I had to walk away from it.”

R: “And then?”

M: “Unbeknownst to me, four years later, they had a change of management at Facebook, and this new person reached out to me thinking, "Oh, this is an artist who I love who's in Miami." And I'm just like, "Did you know you guys reached out to me four years ago for a similar idea, but it didn't work out because of funding?" And so this new person was able to come to a middle ground, and we found a budget that we could use to execute the project.

So to kind of answer your question: When National Brands reached out to me, they're not trying to conform or package me. They're reaching out to me because they like the authentic work that I'm making. And then when they reached out to me, I'm not doing something different from what I'm already making. They're actually embracing it.

I've been seeing in the past couple of years brands are embracing artists, and they're no longer steering away from controversial subjects. Even with Ciroc vodka, which I did a big project with, I did a whole installation on seawater, sea level rise, and they did a whole marketing campaign around water and things like that with their vodka brand.

So, I've found these unique opportunities where I'm weaving my authentic voice, my creative license, and the brands are responding to that, and they're giving me complete agency to take on an element of the brand and kind of push it into a vocabulary where they want to introduce it to their audience.

Yes, I don't think there's a contradiction. If you look at art history, many artists were funded by the church, and they had to paint a certain thing that the church wanted. So, if the brand reached out to you, there's a certain product or there's a certain messaging that they want, but they're giving artists agency of how the messaging and how the story is told.”

R: “God is the biggest brand of all! but I mean, shame on Facebook for not giving you the budget you wanted. That's embarrassing for them.”

M: “Not necessarily, because every corporation has a budget set aside. But I think as artists, sometimes you have to know when to walk away.

Here’s a true story. When I graduated from college, I had an opportunity to create an installation in New York on Fashion Avenue for this luxury Italian brand, and there was something that didn't add up about this commission. Upon doing research, I realized that the brand wanted me to copy another artist's work. And this would have been an $80,000 commission. Imagine, as a fresh college student, and you have an $80,000 commission hanging in front of you, and you're like, "What do I do?" And I asked my department chair, one of few mentors at the time when I was in college.

I ended up walking away from that opportunity because I could either produce, I knew I could do the project because it was set to be executed, so I could either execute this artist's work and copy somebody's work, and that would set the precedent of what I might be known for, or I could walk away and find that opportunities do come back.

I've always been, again, like, you know, trying to find my authentic voice. You know, like, money had this place, you know, but at the same time, you know, you should have a level of self-worth. And there are certain things that, as artists, you should not be willing to compromise so much.”

R: “And I think it's such a give and take too, like, where, you know, it's like working within the climate, um, sector for so many years, you know, like, people who, like, opponents of the space, like, love to be like, "you guys fly to conferences." And I'm not saying we should fly to conferences, but there is this, like, there is a sense that, like, if you are doing anything, actually, what my first episode of this podcast, my lovely guest talks a lot about, like, countering this idea of perfectionism within, like, social change, um, environmental advocacy, activist spaces, like, that, like, we have to counter this perfectionism that, like, you can't work for somebody who can be potentially seen as evil in other areas because we're not living isolated in a cabin. And there was, like, we're part of society as artists, and there is this constant interplay that has to happen, like, where we're constantly asking, like, "does this fit with my values? Can I make this fit with my values?" And just, like, just trying to create a reality where we can feed ourselves.”

M: “absolutely. And, again, you know, sometimes it's okay to walk away from a project, yeah. And when things like that happen, I'm a strong believer that it comes back in other ways, you know? There are projects that I've said no to, and I knew it was the right decision, or it would have compromised the work or the messaging or the final product. By walking away you’re saving yourself from disappointment.”

R: “We’ve been talking forever! Let me try to wrap this up with some shorter questions. Switching gears, looking around at all this plant life, all this interwoven life, in every medium - my eyes have been so happy this entire time. My question is, what is your favorite local flora?”

M: “It’s been changing a lot. Most recently, the hibiscus. I grew up around it in Haiti, and it’s also the national flower for some countries in the Caribbean, including, I believe, Haiti as well.”

R: “And favorite local fauna?”

M: “Probably the chicken! The chicken is such a unique creature you see in Miami. And in our neighborhood there’s also peacocks. Growing up in Little Haiti, it was very common to see chickens and roosters running around. And to hear them at 5 o'clock in the morning.”

R: “In the city! Wow.”

M: “Yeah, in the city.”

R: “I want to go to Little Haiti. Ok, three artists who have had an impact on your life and career.”

M: “At the moment: 1) Didier William, a Miami native, based in Pennsylvania. He’s a painter and does printmaking. 2) Another artist who I love - I love his momentum - and who is much younger than me is Cornelius Tulloch. He’s a recent graduate of Cornell University. He has a background in architecture, photography, and painting. He’s a triple threat, i’m really excited for his future. I see a lot of myself in him. He’s like a younger version of me. 3) Then in terms of women I would say Chris Friday. She’s another local artist, based here in Miami. Her future is really bright. I want a piece from her in my collection.”

R: “Can you share a piece of homework, as an art educator? I also love that you have said that, “art is not separate, that it goes hand in hand with academics”. I love that, it’s so true, we need art in all spaces in my opinion. What would your piece of homework for the audience be?”

M: “Being an educator in the museum space I like inquiry. How inquiry works is that you make a visual observation of the work in front of you. Instead of coming to an immediate conclusion, you analyze a work based on its various aspects before you form a conclusion about the work. Another way of phrasing it is, “don’t judge a book by its cover”. Extend this beyond art too: give people grace, give them an opportunity. By being patient, you may uncover something new.”

R: “That’s so beautiful. It’s such an honor to have had this lengthy interview with you. I can’t wait to explore more and to share more in the podcast accompaniment.”

M: “Thank you, it’s been an absolute pleasure.”

[Music]

That's all for this episode, the first in the two part Miami climate series.. Thank you for sharing this space and time with me & Morel. You can find links to Morel’s work in the show notes, along with the link to the visual podcast accompaniment blog post where Morel shows three of his own pieces that are especially significant.

Please do get in touch if you have ideas for who else should be interviewed here in this forum on art, society, and our planet. With this being such a new podcast, I’d appreciate any support in the form of podcast subscribing wherever you listen, rating, commenting, and of course sharing with anyone you think might be interested in these subjects. I hope you’ll listen to next week’s podcast for part two of this special Miami climate change series.

Thank you to Samuel Cunningham for the podcast editing and to Cosmo Sheldrake for the podcast music, which comes from his song, Pelicans We.

Until next time!

[Music]